Category Archives: NEWS

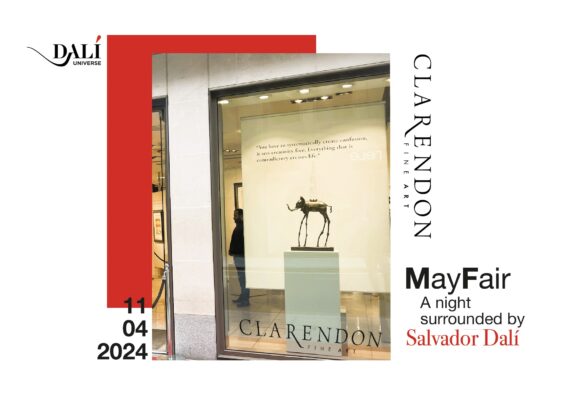

The Master of Surrealism Conquers Mayfair

“Beyond Reality” : Salvador Dalí at Clarendon Fine Art “You have to systematically create confusion,

16

Apr

Apr

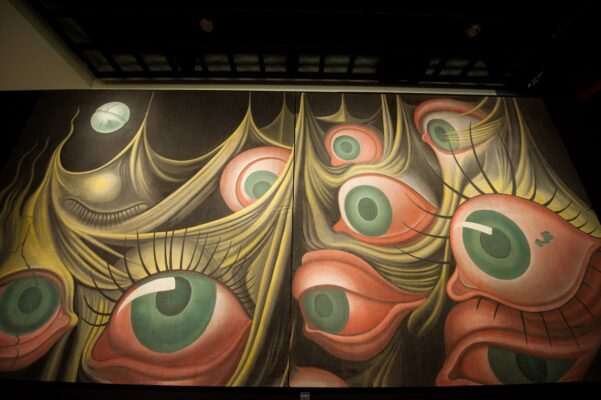

Salvador Dalí: Exploring the Obsession with the Eye.

“Salvador Dalí endowed surrealism with a prime instrument of importance, the paranoid-critical method, which he

04

Mar

Mar

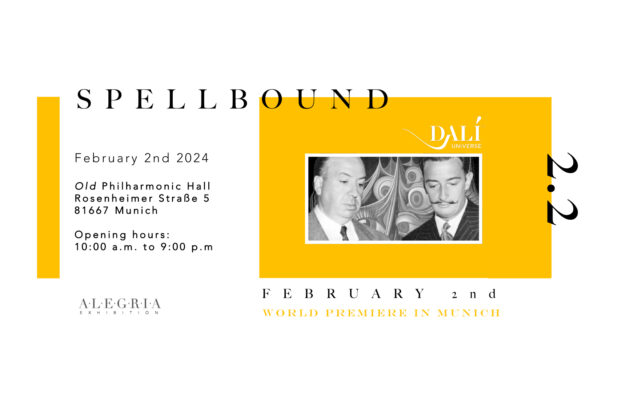

“Dalí: Spellbound – The Exhibition” in Munich, Germany.

“I wanted Dalí because of the architectural sharpness of his work”. Alfred Hitchcock On this

01

Feb

Feb

Dalí Universe at London Art Fair 2024: Mollbrinks Art Gallery pays tribute to Salvador Dalí on the 120th Anniversary of his birth.

The London Art Fair returns for its 36th edition this week at the Business Design

17

Jan

Jan

“Dalí Universe” New Website: Celebrating the Legacy of Salvador Dalí on the 120th anniversary of his birth, 1904 – 2024.

As we usher in the New Year of 2024, we are thrilled to kickstart it

15

Jan

Jan

- 1

- 2